A recent job posting on LinkedIn reads:

Who do you need to be?

- A strong relationship-builder who takes a people-first approach

- A self-motivated and goal-oriented individual with a strong work ethic

- An eager learner with a professional demeanor, excellent presentation and organizational skills

- A candidate for BA/BS degree

What position do you think these requirements were for? Perhaps a Car Salesman?

As it turns out, the position was titled Financial Advisor for a domestic financial services company that generates over $30 billion in annual revenue.

If you had to compose a job description for your own financial advisor, what academic background and skill set would you ask for? Presumably, you would require them to have a deep understanding of finance, the tax code, insurance, as well as the laws that govern retirement plans and estates. More importantly, you would expect them to possess the analytical and critical thinking skills necessary to integrate these intricate concepts into the context of your goals and objectives. Finally, you would demand their dedication and commitment to revisit this analysis on an ongoing basis as your personal circumstances change and the economic/legislative landscape evolves. So how is it possible for an actual job description to omit every single qualification desired by the end client? How could a company thrive by hiring salespeople to do the job of an analyst? The answer is simple — the quality of the advice rendered by a financial advisor is nearly impossible to observe.

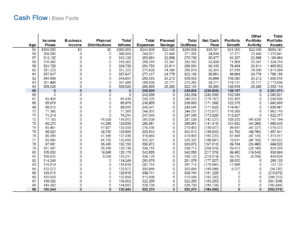

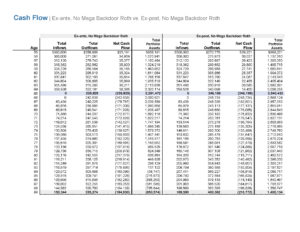

Consider two clients, Jordan and Warren, who walked into their respective advisor’s offices for the first time in June 2011 with the same objective in mind — to retire in 2021 at age 65 and spend $170,000 each year thereafter. They worked for the same employer and shared identical financial characteristics including assets, liabilities, incomes, expenses, and savings strategy. Their 2011 balance sheet and long-term cash flow projections are displayed in the exhibits below:

Exhibit A

Exhibit B

While both advisors showed how their respective plans of maxing out their 401(k)s (Planned Savings) and contributing their excess cash flow of $33,000 annually to their taxable brokerage accounts until retirement would fail at age 84 assuming a 6.5% average annual return on their 60/40 investment portfolios and a 2% rate of inflation, Warren’s advisor was determined to find a way for his client’s portfolio to last at least until his life expectancy of 86 without prescribing any lifestyle changes. After taking some time to peruse the Summary Plan Description of Warren’s 401(k), he discovered the following two provisions which would enable him to do just that:

Section III. Employee After-Tax Contributions

After you satisfy the Plan’s eligibility and entry date requirements, you may elect to contribute a percentage of your eligible compensation into the Plan on an after-tax basis. You may contribute a percentage of eligible compensation up to an annual maximum of 75%.

Section VI. Withdrawals of After-Tax Contributions

If you have previously made after-tax contributions then you may elect to withdraw all or a portion of your contributions. There is no limit on the number of withdrawals of this type.

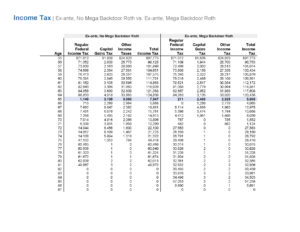

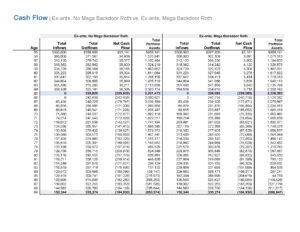

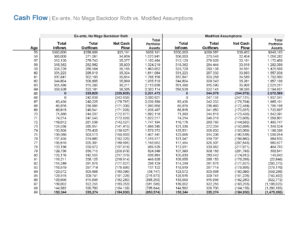

In light of Warren’s eligibility to make after-tax contributions to the plan and immediately withdraw those contributions, his advisor proposed a strategy known as a Mega Backdoor Roth Contribution to take the place of the annual brokerage investments. By redirecting $31,000 of his excess cash flow to the 401(k) after-tax account and immediately transferring it to his Roth IRA, Warren would avoid income taxes on the interest, dividends, and capital appreciation generated by a cumulative $310,000 (in 2011 dollars). Given Warren’s long-term marginal tax rates of up to 35% on non-qualified dividends and bond interest, 15% on capital gains, plus an additional 3.8% on the foregoing until retirement, this strategy projected to substantially decrease his tax expenses over time and extend the longevity of his portfolio by over a year as seen in the tax and cash flow comparisons below. After receiving Warren’s approval, the advisor agreed to implement the strategy and confirm the proper tax reporting from the 401(k) and Roth plans at each year end. Jordan’s advisor simply replaced several of his client’s existing investments with similar ones issued by a different institution.

Exhibit C

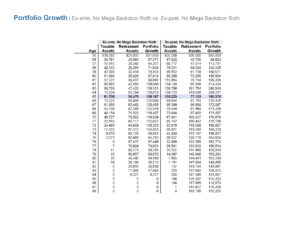

Fast-forward to June 2021, when Jordan and Warren walk in for their respective annual reviews and ask to revisit their retirement projections in the hopes of submitting for retirement from their employers. Due to extraordinary stock market success from June 2011 through June 2021 which saw the S&P 500 earn an incredible 300% total return, both portfolios grew by 10% annually and were now worth roughly $3 million — almost $1 million higher than originally forecast. Jordan does not understand much about market indexes, but is thrilled to see that he is now projected to still have over $1 million left at age 89 per the exhibits below. Warren was aided even more significantly by the bull market and will also feel more confident than ever handing in his letter of resignation.

Exhibit E

Exhibit F

Instead of being forced to compromise on his desired lifestyle because of a missed opportunity, Jordan will likely live out his dream retirement and think highly of his advisor for years to come. While in this case it was historically strong market performance that obscured the inferiority of a financial plan, extreme tax policy, inflation, or interest rates, can all have a similar effect.

The other reason why salesmen are so effective at meeting client expectations in this industry is that they are also the ones typically setting them.

An automotive company hires an engineering consultant to help increase the fuel efficiency of its luxury sedan. An offensive lineman engages a strength coach to help prepare him for the NFL scouting combine. These clients may not know anything about hybrid technology or biomechanics, but they can easily ascertain where they currently stand. The vehicle is currently getting a combined 25 MPG, and the player can only perform 24 bench press reps. Determining your own financial fitness, however, requires the construction of an elaborate model incorporating complex tax conventions, investment concepts, and other parameters — a fairly esoteric exercise.

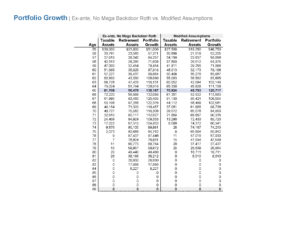

Imagine if at the initial meeting in 2011, Jordan’s advisor would have presented a modified model incorporating the following data points:

- Brokerage account tax basis incorrectly entered as $75,000 instead of $375,000

- Standard deviation of portfolio returns increased from 10% to 15%

The impact of these adjustments on projected portfolio growth and sustainability can be seen in the next two reports:

Exhibit G

Exhibit H

Due to an incorrect input and a controversial assumption neither of which Jordan has the capacity to understand, he is now expecting to run out of money three years earlier at age 81. By understating the tax basis — the amount of after-tax dollars Jordan invested over time which can be recovered tax-free — of the brokerage account by $300,000, this model overestimates the capital gains tax due upon the turnover and liquidation of the account by more than $35,000 over time.

While both the original and modified versions of Jordan’s initial plan both assume an annual arithmetic (average) return of 6.5%, that is not the return either portfolio projects to actually achieve over time. Due to a complex mathematical concept, their respective geometric (actual) returns are mitigated by each portfolio’s variability, or standard deviation. To the extent that the standard deviation of returns is assumed to be higher, realized returns would be lower for a given average return. For instance, if someone invests $100 and earns 10% in Year 1 and loses 10% in Year 2, their average return is 0%. This is true despite the fact that after Year 1 the investment was worth $110 before it lost 10% in Year 2 and fell to $99 — clearly yielding a negative total return. A portfolio that earned nothing in both years i.e. had no variability, would have performed better despite having the same average 0% return. While in the original model Jordan’s advisor assumed a 10% standard deviation— a moderate estimate at the time —this version utilizes a 15% figure, thus reducing the expected return of the portfolio from 6% to 5.5% and contributing strongly to the weaker projection.

Thus, even if market performance had just been average from that point on, Jordan would once again be singing the praises of his advisor for securing him three extra years of funding that were likely already there to begin with. As this narrative illustrates, ascertaining a frame of reference for financial progress is more technical than doing so for many other goals. Without the ability to conceive their own starting point, most clients turn to their advisor to develop an outlook — a conflict of interest if there ever was one. While this case highlights the impact of flawed tax basis and portfolio return assumptions, there are countless others that can be equally if not more impactful.

Now you can start to understand how a company that hires salesmen to be financial advisors can earn $30 billion a year. The acute impact of uncontrollable influences, combined with the acumen needed to ascertain expectations, makes it very difficult to attribute superior outcomes to superior advice and vice versa. Thus, to the casual onlooker, financial advisory can in fact appear a lot like car sales where everyone is pushing similar investment vehicles and it’s just a matter of finding someone relatable and paying the lowest price. To the informed consumer however, it looks more like business consulting where you choose the advisor who will most improve your probability of achieving mutually defined success.

So what implications does this observation have on the way you should approach your financial life? It means that when it comes to your finances, ignorance is not bliss. To the extent that someone remains financially illiterate, they will forever be placing blind trust in someone who has a conflict of interest over whether or not to dig deeper into an existing plan or bring on another client. By contrast, gaining meaningful literacy will allow you to develop reasonable expectations about what you can achieve, distinguish strategy from products and other speculative value propositions, and experience the difference between true peace of mind and not knowing what you are missing. You can choose your advisor based on their integrity and wisdom rather than on their sales skills, or manage your own finances with greater sophistication.

The goal for FiveTwentyNine is to go one step further than much of the existing financial media in facilitating this literacy. While there are a number of existing podcasts, channels, and blogs devoted to introducing basic financial concepts and rules, we will show you how they all fit together. Through the use of numbers, facts, and logic, we will empower you to think more intelligently about your most pressing big picture objectives. We encourage you to subscribe and invest 1 hour a week to ensure that the other 50+ you spend working are as productive as possible.

Because if you don’t, chances are no one else will.