The first segment of this publication proved how quickly and accurately collective wisdom bids prices up or down in response to macroeconomic and company-specific developments, mitigating the ability of an investment advisor to consistently achieve returns beyond that which is already built into these prices — or their E(r). There are no market forces, however, that undermine the efforts of a financial planner seeking to manage the risk, taxes, fees, and liquidity associated with these expected returns. Given that these aspects of investing rely on absolute rather than relative intelligence, its practitioner need not demonstrate the superiority of his past achievements, but rather the soundness of the assumptions and reasoning behind his current ideas.

Idiosyncratic, or single-stock risk may not matter for the purposes of security pricing, but it absolutely matters for the purposes of portfolio construction. While the market may not discount an investment based on its individual risk characteristics because they can be diversified away — you still have to actually diversify them away. Utilizing yet another Nobel-prize winning framework known as Mean-Variance Optimization, a financial planner can reduce this risk without compromising on return.

While the return of a portfolio may simply be the weighted average of its underlying investment yields, the same thing cannot be said about its level of volatility. To the extent that its assets are uncorrelated or negatively correlated with each other, a portfolio’s risk will be lower than the sum of its parts. For example, the historical correlation between Tesla and ExxonMobil has been about -.5 — presumably because every positive development in the electric car industry is bad news for the oil industry. This means that when Tesla outperforms its average return, ExxonMobil underperforms its mean by about half as much and vice-versa. Although both stocks may experience significant volatility, there is a limit to how much the value of a portfolio holding both of them could fluctuate during a particular period. Thus, as long as each stock generates returns commensurate with its non-diversifiable risk, this two-asset portfolio must provide a better ratio of total risk to return than either one could achieve by itself.

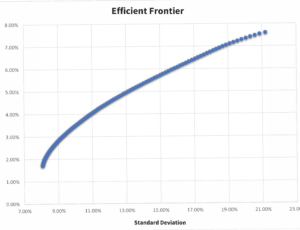

The sample efficient frontier below illustrates this concept on a much broader scale. By incorporating the expected returns, standard deviations, and correlations of several baskets of assets from large-cap stocks to high-yield bonds, this model yields a series of portfolios that minimize risk for a given expected return, or maximize return for a given level of risk. To the extent that a portfolio lies below this line, its efficiency could be improved by adjusting the weightings of its underlying assets. Given that these portfolios are well-diversified and thus feature minimal idiosyncratic risk, those with higher volatility yield higher expected returns in accordance with mainstream academic research. The frontier is not linear, however, because certain combinations of assets — particularly those in the middle of the frontier — correlate more favorably with each other.

While mean-variance optimization might enable a financial planner to efficiently hedge portfolio volatility, it does not shed any light on the appropriate amount of risk each of his clients should actually take on. To make this determination, another analytical tool known as Monte Carlo analysis is necessary.

Imagine someone offers you $6,100 for every seven you get on a roll of two dice, with a cost to you of $1,000 per roll. You are allowed an unlimited number of rolls. You recognize that the probability of getting a seven on a roll of two dice is 1 in 6. While you quickly calculate that the expected revenue of the roll is more than the $1,000 cost, you cannot afford to lose any money and you have a train to catch in ten minutes. You realize you could easily not get a seven 1/6 of the time with such a small sample size, and you wish you had a quick way to know how many rolls would be necessary to all but guarantee this as a winning proposition.

This is where Monte Carlo analysis would be useful. Within seconds of entering the various inputs of this deal into a simulation engine, you could determine the number of rolls necessary to achieve a given probability of making money. The engine would simulate the rolls in advance without you having to commit to the offer and thus allow you to make a more informed decision.

This same framework can be used to ascertain an investor’s risk capacity, or the extent to which their financial needs are immune to interim fluctuations in the value of their assets. While over short time horizons a portfolio might yield returns that stray far from its expected output, its results become more predictable as the sample size of time grows larger. By simulating a client’s lifetime using efficient portfolios with varying levels of normally distributed risk and return, a financial planner can identify an allocation that is conservative enough to prevent their portfolio from being eroded prematurely by a few bad rolls, but aggressive enough to fund their long-term objectives. Of course, if an investor cannot emotionally withstand the market downturns associated with a particular allocation and would be inclined to sell before a potential recovery, they would be better off with a more stable alternative even if it is not optimal from a risk capacity perspective.

Once an investor has determined the most appropriate overall mix of assets needed to fund a particular objective, they may have the opportunity to craft strategic sub-allocations across various accounts via a concept called asset location — as distinct from asset allocation. By coordinating the concept of compound interest with tax law, an investor can increase their after-tax rate of return without ever opening a Wall Street Journal. For those in high tax brackets, this could mean placing investments that would otherwise generate substantial, currently taxable income such as bonds in tax-sheltered retirement accounts, while housing assets subject to subsidized, deferred tax rates such as growth stocks in non-qualified, brokerage accounts. Of course, this strategy would only be effective to the extent that these brokerage accounts are managed passively enough to avoid tax-inducing turnover, and assuming that the liquidity and penalty issues associated with premature retirement plan distributions are not anticipated. Alternatively, municipal bonds can be utilized to negate interest income taxation — an especially compelling strategy for those who live in high income tax states. Roth or Health Savings Account owners with plenty of liquidity might be best suited to harbor their riskiest, highest-yielding investments in these tax-free environments, while those with limited risk capacity might not yet have the luxury to do so.

Tax “alpha” can also be generated in the process of maintaining or adjusting a portfolio strategy over time, through shrewd application of the laws surrounding capital gains taxation. This planning opportunity most commonly arises when particular asset classes have outperformed others — resulting in allocations that are no longer in line with their respective optimal weightings. While there will always be some degree of tension between correcting these imbalances and limiting taxes, there are a number of practices that can help an investor achieve the best of both worlds. Those who are still accumulating assets can look to rebalance by using ongoing savings to purchase the positions that have lagged behind. Those who are either over the age of 72 or have inherited retirement accounts can use the cash that is mandatorily forced out of their IRAs and other qualified plans to do the same. More recent retirees can potentially shelter a portion of these gains using their 0% capital gains bracket. Some individuals may be able to offset current gains with losses that were disallowed in prior tax years.

Given that the efficient frontier is not linear, there are some imbalanced portfolios that are less detrimental than others — such as those that feature less than optimal sub-allocations but are still in line with their broader categorical targets. While it may be prudent to wait until the end of a high-income tax year to correct an international small-cap allocation that is 2% above its target, it would be harder to justify this approach with respect to a 7% overall equity imbalance. Not only might this latter discrepancy move a portfolio either off of or to a highly inefficient part of the frontier, it could also yield a standard deviation that is too extreme for its owner’s risk capacity.

Once a decision to trim a particular investment has been reached, an investor can sell shares that were initially purchased or reinvested at higher prices and thus feature less embedded gains, and stay away from those that were bought when the security was down and/or would yield short-term capital gains.

A final way that a financial planner can help a client maximize returns is to generate premiums associated with investment illiquidity. To attract investors to securities issued to finance illiquid ventures and are thus not redeemable within the typical 1-2 day period afforded to traditional investments, capitalists often need to offer them discounted share prices. By maintaining a modest allocation to these more unorthodox vehicles, an investor can extract additional returns without increasing a portfolio’s beta.

While an investment advisor might employ a variety of tactical vehicles such as actively managed funds or stock selections to actually obtain exposure to a desired asset class, a financial planner is most interested in controlling costs. From the latter’s point of view, it makes little sense to incur the sales loads, expense ratios, 12b-1 fees, or other custodian-imposed transactional expenses needed to gain access to the latest top-performing fund manager, in light of the onerous due diligence that would be needed to determine if this success is likely to continue. Instead, he would be more inclined to utilize indexed investment options that carry little to no costs via custodial platforms such as Schwab or Fidelity, while also benefiting from the administrative support these custodians provide.

Despite the fundamental soundness of the investment planning approach described above, an entire industry has been developed to profit from the one thing standing in the way of its universal adoption — fear. By highlighting the empirical struggles of the frameworks introduced herein, and framing market risk as a discrete distribution rather than a continuous one, insurance salesmen have thrived under the easily accessible title of financial advisor for decades.

The typical pitch of an annuity or life insurance-driven investment plan starts with a worst-case market performance scenario based on a historically brutal time period. Aside from being built with misleading assumptions, such models encourage investors to hide from unlikely, catastrophic outcomes rather than make calculated trade-offs between achieving certain milestones and putting more basic expenses at risk. By focusing on the severity of a prolonged market crash rather than estimating the extent to which it is likely to happen, advocates of annuities and other policies with guaranteed minimum returns ignore asset allocation analytics in favor of a one-size-fits-all approach to managing investment risk.

To support this more rigid, contractual philosophy, insurance agents quote studies that have not been supportive of the idea that beta drives investment returns — which would undermine the CAPM and, in turn, the risk and return assumptions used to construct efficient portfolios and Monte Carlo models. They conclude that much like the risks of premature death, permanent disability, home destruction, and car accidents, market downturns cannot be self-insured. The same way we all happily part with the profits that insurance companies make on our home, auto, life, and disability premiums in exchange for taking on risks that we cannot handle ourselves, they argue, we must also be willing to pay to protect against the immeasurable losses that might occur in our portfolios.

This mantra has several flaws. First, it fails to acknowledge that more modern adaptations of the CAPM such as the Fama and French Three Factor Model do not replace beta with other catalysts of investment returns — but simply add to it. Furthermore, it fails to address the impact that insuring market risk may have on other elements of financial uncertainty such as runaway inflation or unanticipated expenses. While a market insurance policy may protect the nominal value of a portfolio, its rigidity and limited upside can nevertheless jeopardize an investor’s bare necessities in real terms. Lastly, it implies that no degree of volatility would impact a guaranteed product, when in fact many contract value assurances are considered part of an insurer’s general account and are thus only as secure as the financial stability of the company and its reinsurance program.

As the above exposition demonstrates, the portfolio advice rendered by a financial planner is nothing like that of an investment advisor. While alpha must be negative on average and is nearly impossible to detect in advance, the anticipated impact of risk-driven, tax-efficient investing can be appreciated by anyone willing to read up on how markets function, how portfolios are taxed, and how to make intelligent decisions under uncertainty.